The Protestant Church of St. Paul In Clogheen Co. Tipperary, has today been reduced, like so many Protestant Churches in Ireland, to the status of a Community Centre.

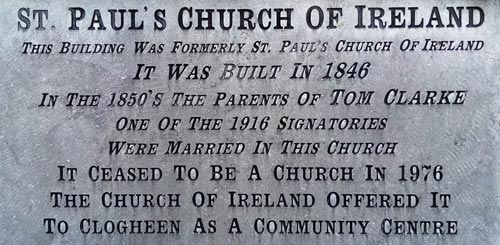

According to a plaque over the doorway in the porch; the former Church dates back to 1846, the first full year of the Great Famine (1845-1849) and was closed officially in 1976.

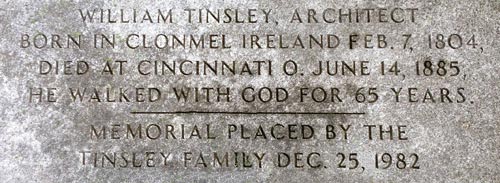

The building, showing every evidence of high quality early nineteenth-century craftsmanship and design, is associated with Clonmel, Co. Tipperary born and renowned architect, William Tinsley. Tinsley you will remember, in 1836, also constructed the Chapter House, once home to the Bolton Library, in Cashel, Co. Tipperary.

Architect William Tinsley: William Tinsley served as a juryman in the William Smith O’Brien trial, held in Clonmel in 1848. O’Brien, then leader of the ‘Young Irelanders’ had been arrested at Thurles Railway Station, and following his trial was convicted of sedition for his part in the “Ballingarry (South Riding) Uprising“ near Thurles, [“Battle of Widow McCormack’s Cabbage Patch”] in that same year.

Although an independently wealthy property owner in Clonmel, it is thought that his known association with the William Smith O’Brien trial as a Juryman, together with Great Famine conditions, may have contributed to a decline in Tinsley’s business. Same is understood to have resulted in his decision, in 1851, to emigrate to Cincinnati, Ohio, US, with his second wife Lucy and their nine children. His first wife, Ellen MacCarthy, had died of tuberculosis after just two years of marriage. He then had married her cousin Lucy MacCarthy, latter who died in 1857 in Indianapolis, Indiana. His third marriage, to Mary Eliza Nixon, ended in estrangement. In total he had fathered seventeen children by his three wives. Following his death in 1885, he was interred at Crown Hill Cemetery, Indianapolis, Indiana, US.

A short distance from the Church, Tom Clarke, [Tomás Séamus Ó Cléirigh], was born on March 11th, 1857, in Main Street Clogheen, Co Tipperary; the son of Irish Catholic servant girl Mary Palmer and Irish Protestant British Army Sergeant James Clarke. Two months later the couple married in this same St. Paul’s (C of I) Church, at Lower Main Street, Clogheen Market, Clogheen, South Co. Tipperary, (Picture shown hereunder). Over the next 12 years together Mary and James would add two girls and one other boy to their family unit.

In 1865, after spending some years in South Africa, his father Sgt. Clarke was transferred to the Ulster town of Dungannon, County Tyrone, Ireland, and it was here that Tom spent his formative years, bonding strongly with both his parents and siblings.

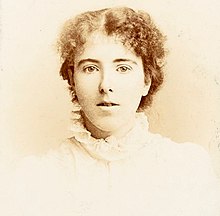

Photographer: G. Willoughby.

Highly intelligent; whose hero was Theobald Wolfe Tone, latter a leading protestant Irish revolutionary figure and founder members of the republican society known as the United Irishmen, Tom Clarke went on to became an assistant teacher at a local school, while developing a passion for politics.

Rejecting only his father’s British Army uniform; Tom Clarke was constantly warned by his father James, that defying the might of the Great British Empire, was completely futile. However, being naturally rebellious and sympathetic of the rough treatment issued out to Dutch, German, and Huguenot settlers (Boers) in South Africa, Tom had come to regard the British Army stationed in South Africa as ‘an imperial garrison of oppression’ since the area came into their possession in 1806, as a result of the Napoleonic wars.

For centuries the Irish town of Dungannon had been a den of bitter religious hatred and political antagonisms between Catholics and Protestants. In 1878 Tom heard a speech by the national organiser of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) John Daly and a short time later, at the age of 21years he joined the organisation, having come to the realisation that his future must involve attempts aimed at the destruction of every vestige of British authority within Ireland.

By 1880, he had risen to be head of his local Irish Republican Brotherhood group. It was at this time that an RIC officer had shot and killed a man during riots between the Orange Order, (latter a Protestant fraternal order) and the Ancient Order of Hibernians, (latter a Roman Catholic organisation).

A revenge attack by Clarke and his followers on the RIC in Irish Street, Dungannon failed; forcing Clarke, who now feared arrest, to flee to New York, where he soon joined Clan na Gael, the then leading republican organisation in America. Eager to strike at the very heart of the British Empire, he volunteered to join the Fenian dynamite campaign (carried out in England between the years 1881 and 1885). This campaign had been advocated by Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa, one of the IRB leaders, also then exiled in the United States.

In 1883, using the alias “Henry Wilson”, Clarke was sent to London. However, aided by paid informants, British authorities were already on the heels of those involved. Clarke was arrested while found to be in possession of dynamite, as were three of his associates. He was sent for trial at London’s Old Bailey, before being sentenced to penal servitude for life, on May, 28th 1883.

He would serve 15 years in prisons Pentonville, (Islington, Central London), Chatham, (St. Mary’s Island Kent) and Isle of Portland prison, (Dorset) before his release in 1898. Following years of invasive body searches, systematic sleep deprivation and constant isolation, his hatred of the British establishment made him even more determined to continue in his efforts to overthrow British rule in Ireland.

Released and now 41-years-old, he moved to Brooklyn in the United States, where he would be later be joined by the very lovely Kathleen Daly; the 20-year-old fiercely republican niece of his aforementioned mentor and prison comrade John Daly. Despite their age difference they were subsequent married on July 16th 1901, in New York City.

Kathleen Clarke (née Daly) would become a founder member of Cumann na mBan in 1914 and later subsequently a Teachta Dála (TD) and Senator with both Sinn Féin and Fianna Fáil, and would become the first female Lord Mayor of Dublin (1939–41).

In late 1902 Kildare born John Devoy the then leader of Clan na Gael, conscience of Clarke’s organising ability, appointed him the editor of his weekly newspaper “The Gaelic American”, which documented the struggles of Irish Americans and was published in the United States from 1903 to 1951.

John Devoy was one of the few people to have played a role in the Fenian Rising of 1867, the Easter Rising of 1916 and the Irish War of Independence of 1919–1921, and had orchestrated the escape of IRB founder and Kilkenny born James Stephens from Richmond Prison in Dublin. Following his death in 1928 The Times of London newspaper described Devoy as, “the most bitter and persistent, as well as the most dangerous, enemy of this country which Ireland has produced since Wolfe Tone”.

Tom proved to be a talented journalist and his anti-British propaganda soon attracted 30,000 readers across America. Under the intensive instruction of John Devoy, Clarke learned the valuable techniques on how to manage a revolutionary organisation; how to manipulate people and when to exercise power.

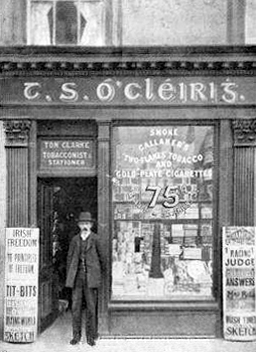

Tom Clarke returned to Ireland in November 1907, opening a small newspaper, stationers and tobacconist shop at No 55 Amien Street, Dublin. Within the next 5 years he had successfully rid the IRB of its entrenched older individuals which formerly made up what Clarke saw as a failed supreme Council and had befriended Sean MacDermott, a younger man who shared his love of conspiracy and revolutionary ideals.

With the start of the first World War in August 1914, Clarke and MacDermott both saw their opportunity and established a military council made up of Patrick Pearse, Joseph Plunkett and Eamonn Ceannt to secretly devise plans for a rising, supervised by Clarke himself and MacDermott. In January 1916 Clarke forged an alliance with James Connolly, informing him of most of his Military Council’s plans.

The agreement by Germany to supply a shipment of arms for a rising on Sunday, April 23rd, 1916, seemed to place everything in position. However, as we now know, Volunteer President Eoin MacNeill countermanded the parades that were to precede the uprising. Clarke’s Military Council however decided to proceed on Easter Monday in the hope that the nation would respond. There would be no real response.

The Easter 1916 Rising began on Easter Monday, April 24th 1916 and lasted for six days, ending on April 29th, 1916.

Of the 485 people killed, 260 of these were civilians, 143 were British military and RIC personnel. Irish rebels deaths made up 82 in total, including 16 rebels executed for their roles in the Rising. More than 2,600 individuals were wounded, with many of the civilians either killed or wounded by British artillery fire mistaken for rebels or caught in the crossfire during firefights between the British and the rebels.

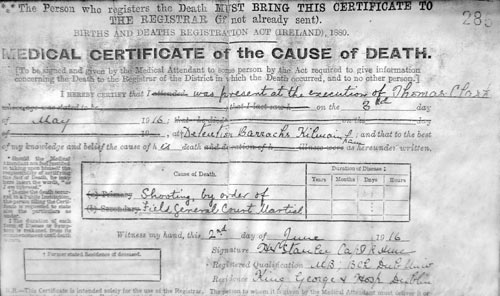

Tom Clarke’s court martial on Tuesday May 2nd lasted approximately 15 minutes. He made no statement, called no witnesses and only entered a plea of not guilty, so as to deny being a German agent.

Found guilty and sentenced to death, early the next day he was brought with Pearse and MacDonagh to Kilmainham Gaol. In the morning he was allowed a final farewell visit from his wife.

Shortly before 3:00am he entered the stone-breakers’ yard and after vainly offering to forego a blindfold, he was executed by a 12-man firing squad as was Pearse and MacDonagh; all in quick succession.

A horse-drawn ambulance was used to carry the three corpses of the executed men to Arbour Hill for interment in unmarked graves in the exercise yard of the military prison, behind what we today know as Collins Barracks. The buildings now house the National Museum of Ireland (Decorative Arts and History).

A request by his wife and three sons to have Tom’s body taken for interment to a family plot, was rejected by Colonial Governor, General Sir John Grenfell Maxwell, latter who had played a key part in the response to the 1916 Irish Easter Rising, including the ordering of the execution of all leaders of the rising.